The Blossoming of sedgeflowers | MANTRA

by Ryan MacEvoy McCullough

Part I—Galaxy

The greatest challenge in talking about twentieth century music is how such an artistically diverse era is so misleadingly encapsulated as one coherent musical epoch. Earlier historic periods in the Western Classical tradition certainly featured notable divides — the aesthetic chasm between the acolytes of Wagner and Brahms, for example, is a tension that defines music in the late Romantic era — but where these deviations could be seen as analogous to the way old glass ripples and deforms with age, the twentieth century can be best described as the introduction of old glass to a wayward baseball: lightning fissures forming distinct islets, each erratically spinning into space like translucent grenades. That we think of this era as one contiguous whole — conveniently measurable in a neat base ten value — is a backhanded acknowledgement of just how wildly diverse it really was: less of a neatly stretched canvas than an industrial-sized dustpan called on to collect the shards.

If there was any musician from this era who might be best described as the ‘broom’ to our metaphorical dustpan, the German high-modernist composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007) is unquestionably the best candidate. No other artist in the twentieth century was as daring and willing to embrace new ideas and techniques, many diametrically opposed. In this sense, Stockhausen is something of a bellwether and model for the musical challenges facing young composers in the twenty-first century: what to do with a near-infinite buffet of choices, where most paths appear equally rational.

Music in the early decades of the twentieth century carried utopic ideals and assumptions about the progress of music as parallel to the progress of nations, along with a naïve belief that any new developments would be fully absorbed into mass culture. After all, the growth of the middle class in nineteenth-century Europe led to a proliferation of instrument manufacturers and an entire music publishing industry aimed at home audiences awaiting new works by the likes of Wagner and Brahms. Children of this time would have included composers like Claude Debussy, Igor Stravinsky, and Arnold Schoenberg, the holy trinity of early musical modernism, each of whom was steeped in the phantasmagoric psyche of the late nineteenth century. It didn’t go far enough is the refrain heard in their work, a sense that the music of the past had the right idea, but was held back by inadequate or misguided visions.

This falls in stark contrast to music in the post-WWII era. Children of the 1920s and 30s would have just witnessed the modernist utopian ideals of their forebearers gaze on coldly as the old world destroyed itself for the second time in a generation. We can’t change fast enough is the refrain heard in their work, a sense that the music of the past was poisoned by the Right’s ideas, a movement with a clear vision held back by the sheer weight of their ambitions.

This is the context in which the young Stockhausen begins his galactic musical journey. The Second World War is a profound personal tragedy for Stockhausen, still a teenager when the war ends. His father, conscripted to military service, is presumed killed on the front lines. His mother, sent to a mental institution after a nervous breakdown, is euthanized by the Nazis. Stockhausen himself serves as a stretcher-bearer near the front lines at the war’s end, witnessing firsthand the gruesome atrocities of modern conflict. He comes of age at a time when it is easy to view the past with profound suspicion. Worse even than the past, however, is intuition, that handmaiden of prejudice.

This is partly why the early 1950s looms so large in the broader cultural understanding of the avant-garde. This is the era of bleeps and bloops, of music generated by chance and serial procedure, music that is literally about alienating and subverting the self. The less human the better is the refrain easily heard in this work, where every component of musical expression is vaporized and reconstituted (not unlike the social recalibrations mandated upon Teutonic peoples under the Marshall Plan). Even composers like Olivier Messiaen and Stravinsky, now well-established guardians of the old modernist order, are forced to change. Yet it doesn’t take long for the young generation of pioneering composers, Stockhausen among them, to recognize the beginnings of a new musical opportunity: whatever interest lies in these highly formalistic works is the tension that develops between the introduction of rigid structures to that wayward-est of baseballs, the human condition. The collisions inherent to this relationship — of flesh and machine, freedom and structure, form and improvisation — generate complex artifacts no artist could have imagined, let alone notated.

Stockhausen’s work goes through profound shifts throughout the 1950s and 60s as he appears to search for the perfect balance of these relationships. Even early serial works like KONTRA-PUNKTE (“Counter-points,” 1952) and KLAVIERSTÜCKE I-IV (“Piano pieces,” 1952) behave like small operas, where the characters are individual tones. The Dutch pianist Ellen Corver said Stockhausen frequently sang the complex lines from these works in their coachings, a testament to his commitment to every note on the page. Later, GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE (“Song of the Youths,” 1955–56) and KONTAKTE (“Contacts,” 1958—60) place human frailties in relief against monolithic electroacoustic elements, highlighting those uncanny valleys where the two separate worlds meet. The voices of children, so central in the former work, feel especially poignant given Stockhausen’s own perilous youth. The voice itself becomes the focus of STIMMUNG (“Tuning,” 1968), 70 minutes of six singers exploring the expressive potential of drones carefully calibrated to the overtones of an (unheard) low B-flat, an homage to so many vocal traditions of the central Asian continent. Stockhausen even takes a sharp turn back towards intuition, no longer trusted passively, but observed closely like an alien specimen under a microscope. Works like AUS DEN SIEBEN TAGEN (“From the Seven Days,” 1969) and FÜR KOMMENDE ZEITEN (“For Times to Come,” 1968–70) feature collections of entirely textual compositions, prose-poems asking an unspecified number of performers to meditate acoustically on elements of music that can only be imagined. “Play a vibration in the rhythm of the universe” is one of the most famous lines from these works, a beautiful and evocative sound-image, laughably difficult to notate by conventional means.

These are just a few highlights from a vast catalogue spanning 20 years of work, but there is no question that the Stockhausen of 1952 is light-years removed from the Stockhausen of 1969. Over this time, his music curls sharply inward, the scientific objectivity of the early 1950s growing in on itself like an ancient vine. A mental breakdown in the late 60s brings him to the brink of suicide, plagued by bouts of insomnia and self-starvation. The works of Hindu mystic Sri Aurobindo prove to be something of a salve for Stockhausen’s fractured psyche. Aurobindo himself was something of a blended contradiction, a child of the British Raj who spent much of his childhood in an Anglican boarding school in England steeped in the smells and bells of Henry VIII’s church. Aurobindo’s return to India as an adult, and eventual submersion in Hindu mysticism, is from the perspective of a chimeric mind, the fusing of both into one and the same that is so central to mystical thinking. This mode of thinking is key to restoring Stockhausen’s imagination at its lowest point, and he surely sensed that change was in the air.

It is a timeless adage that children rebel against the desires of their parents, only to become their carbon copies later in life. The same could certainly be said for music in the twentieth century, in which cycles of conflict and disintegration seem to rhyme across decades. For composers born in the 30s and 40s, the disintegrative techniques of the early 50s are now an established order, enshrined in their musical educations like a holy liturgy of musical ethics. Polemical proclamations like Pierre Boulez’s infamous 1952 remark about useless (“inutile”) musicians unmoved by the necessity of serial composition fall upon ears less burdened by the traumas of the 1940s. For many of these young composers, the Stockhausen they know is the Stockhausen of the early 50s, powerbroker of a new world order just as tyrannical as the one that came before.

The new stylistic break that occurs in the 1970s is in direct opposition to this perceived new world order. American composers including John Adams, Philip Glass, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, and La Monte Young look towards the boundless creativity occurring not in the electroacoustic studios of Stockhausen’s legendary stomping grounds, the WDR (Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln), but rather Abbey Road studio in London, Sun in Memphis, Motown in Detroit, among many other centers of the formerly “degenerate” music. This shift in attention feels as subversive as what writing music like that of young Stockhausen was supposed to feel like, according to their teachers, but never did. In parallel, a group of Messiaen’s students — including Hugues Dufourt, Tristan Murail, and Gérard Grisey — are striking out on their own path against the prevailing winds of serialism, treating sound itself and basic principles of psychoacoustics as alchemical founts of musical inspiration. It is also in this moment that “historically informed performance” (HIP) begins to take off, a movement that in its early days experiments with ancient instruments like young rock bands “plug in” to Moog and Buchla’s new synthesizers. For all these camps — Minimalists, Spectralists, and HIP practitioners alike — the sensuality of musical experience is placed above all other considerations, becoming a liturgical rule unto itself. They, too, will have rebellious students.

Just as much of the music in the first half of the twentieth century was looking over its shoulder at the shadows of the nineteenth century, it is arguably at this crepuscular moment in the late 1960s and early 70s — rife with social change, protest, and political awakening — that the “twentieth century” ends, and the “twenty-first century” begins. It is also at this moment that Stockhausen writes his groundbreaking MANTRA (1970), a work he describes as a musical galaxy: a vast structure encompassing unbridgeable divides.

Now we turn to composers born in the 1980s and 90s (and beyond). They have come of age in a time when any amount of information on any subject is increasingly available anytime and anywhere, information retrieval is becoming a commodity, and any music can be listened to on demand in any setting, without any presumption of prejudice or judgement. They stare at this pile of broken glass (and the offending baseball) all jumbled together in the industrial dustpan. Where the baseball came from is not anyone’s concern, nor a desire to return the shards to their original housing. But each of these shards catches its own glimpse of the reflected sky, visible only from the viewer’s perspective: a small gateway to another world.

Part II—Solar System

In many ways, the aesthetic consequences of music’s fracturing in the twentieth century are captured in Stockhausen’s musical vision for MANTRA: a humble melody, shattered into many component parts, where each shard is a gateway to its own unique universe. When Andrew and I first started playing MANTRA, we quickly realized that an essential part of highlighting these musical fractures would be to invite reflections from musical voices in our latter generation of composers. The first half of this album is (the beginnings of) that project.

Emblematic of this creative attitude is American composer John Liberatore’s titular work, Sedgeflowers, written in 2017 with support from a Fromm Foundation commissioning grant. John’s music — always subtle, colorful, and, above all, concerned with the joyous playfulness of creative work — seemed a natural fit with the childish gameplay at the core of MANTRA. Writing about the beginnings of Sedgeflowers, John reflected on wanting to evoke the “beguiling” musical materials of the Stockhausen without drawing on its more “high-modernist” associations. While researching another work, John stumbled across this short poem by the fourteenth-century Kashmiri mystic Lal Ded:

Coursing in emptiness,

I, Lalla,

dropped off body and mind,

and stepped into the Secret Self.

Look: Lalla the sedgeflower

blossomed a lotus.

—Lal Ded (14th Century), translated by Coleman Barks

The idea of the sedgeflower — a stiff, stocky grass-weed that might otherwise be dismissed as an invasive pest — blossoming into a colorful, drooping inflorescence became something of a metaphor for the creative process that plagued John’s new work: idea after idea tossed aside, until the humblest, scrap-like of beginnings (a hocketing interplay of intervals from a D major chord, as simple and infectious as a nursery rhyme) began to blossom into the glistening work heard on this album. John describes the process of cultivating this “little weed” as quasi-spiritual, “a kind of inner monastic cultivation, the weed becomes something special, something striking, and beautiful like a lotus.” Like any mantric practice, much of that monastic cultivation comes from a near-endless stream of varied repetition, figures gradually morphing and fooling the ear into revealing hidden counterpoint, highlighting the listener’s active participation in creating meaning for this work.

“Sedgeflowers” began to take on broader meaning for us, reflective not just of John’s own creative process, but of a generational relationship to musical traditions of the past: small, borrowed fragments like seeds for future cultivation. For reasons that should be fairly obvious, Andrew and I were unable to premiere Sedgeflowers as planned in 2020. As we languished at home, awaiting a broader cultural epiphany on social responsibility (which, for reasons that vary wildly depending on political persuasion, has still not materialized), we reflected on another looming cultural milestone: the 250th birth year of Ludwig van Beethoven. Stockhausen has frequently been evoked as a spiritual successor to Beethoven, a composer whose appetite for musical experimentation was driven by a universalistic view of the human spirit. Celebrations of Beethoven were understandably muted as the chaos of 2020 progressed, not least of all because of a growing call to amplify the music of historically marginalized voices over those who were already well-lauded. The question of what Beethoven meant at a time when so much of Western culture felt unmoored from its canonic tethers depended on which fragment of sky you saw in the dustbin shards.

With support from the Cornell Center for Historic Keyboards, Andrew and I developed a commissioning project, RAGE: Vented, anchored around Beethoven’s most scrap-like of compositions, the “Rondo alla Ingharese quasi un capriccio” in G major, op. 129, more commonly known as Die Wut über den verlorenen Groschen, ausgetobt in einer Caprice (“Rage Over a Lost Penny, Vented in a Caprice”), written in 1795. This piece seemed to capture the mood we were all feeling in the summer of 2020: helpless, smothered in anxiety, isolated, prone to nihilistic sarcasm, and imbibing in and out of toxic boredom. We asked six composers — Angus Lee, Dante De Silva, Aida Shirazi, LJ White, Christopher Castro, and Laura Cetilia, with additional contributions by Andrew and myself — to offer fleeting musical soliloquies in the form of variations on this piece, reflecting on what Beethoven meant to them in this wild historic moment. Still dealing with institutional restrictions on visitors, Andrew and I gave the composers one technical stipulation: we would have to record our respective parts separately and mix them “in the box,” a requirement that was both restriction and opportunity.

Yi-wei Angus Lee’s contribution, Rage Over Lost Time, felt like something of a visit to a consignment store: old, worn bric-a-brac stacked on yellowing shelves, paint peeling, springs and hinges rusty and irreparable, fluorescent light contrasting with clouds of dust illuminated by golden hour sun. Lee asked us to spend most of our time “inside” the piano, striking its innards with cimbalom mallets, rubber balls, and plastic hammers, plucking and muting strings with our fingers, and otherwise alienating the instrument from any semblance of its traditional self. A brief fragment of the Beethoven is played at the miniature’s conclusion, conventional piano sound now so foreign that, in this context, a G major triad feels like a crude vulgarity.

Dante De Silva was looking forward to writing something angry and aggressive, but as our favorite year progressed, and a particularly heated election came and went, De Silva felt his need for artistic retribution slowly morphing into a kind of opiated indifference, “a quasi-dream state paradox in which one wants to simultaneously act and not act or think and not think.” To capture this feeling in Too Sedated to Rage, De Silva allowed bits of Beethoven to cross-breed with fragments of Bach’s Aria from the Goldberg Variations and Satie’s Gymnopédie no. 1, both works also anchored on G major, yet with vastly more somnambulant moods. Both pianos are electronically treated to digital delays and amplitude modulation, reminiscent of some particularly psychedelic moments in MANTRA that similarly lull us into a sense of timeless repose.

Aida Shirazi’s take on the Beethoven, RAGE: Screamed, RAGE: Stolen, RAGE: Silenced, looks far more outward, capturing the sense of social obligation felt in the face of massive cultural movements. “A love letter to those whose raised voices are silenced or hijacked,” Iranian-born Shirazi asks the pianists to mute specific upper octaves in the piano with tape and putty, creating a percussive choking sound akin to a rainy deluge on a soft surface, if each raindrop were the distillation of an individual’s frustrations. As the work progresses, individual notes from the Beethoven start to poke out of the texture, fragmentary, not yet formed into a musical phrase, as if to optimistically suggest that a torrent of muted voices can have the effect of eventually eroding its shackles.

LJ White similarly explores the idea of distillation, only here stripping the Beethoven of its angular rhythmic exterior and exposing a kind of soft, liquid underbelly, like an early-morning improvisation at a just-emptied bar. White’s title, Rage is the bodyguard of sadness, is the adaptation of a thought he encountered on social media, “angry is just sad’s bodyguard,” and a reflection on how creative work represents a central mechanism through which artists cope with the difficulties of isolation and political anxiety.

In Andrew Zhou’s note for Con variazioni, he quotes the poet Claudia Rankine, highlighting “bracing clarity and bone-weary frustration”:

I don’t understand how all the history and learning and conversations that have carried us through our lives allow us … still to not see the same things, when they seem so obvious.

…We’re all looking at the same document and you’re still hearing a justification for the killing of black people.

A document in madness, thoughts and remembrance fitted.

—Laertes (Hamlet, Act IV, Sc. 5)

Andrew calls his variation “a doublespeak berceuse—a stupefying lullaby,” in which obsessive references to Beethoven (including works beyond the originating Capriccio) take turns interrupting each other until “everyone around him, exhausted, tumbles and dissolves back into the earth.” Towards the end, we hear a minor version of the famous opening to Beethoven’s “Emperor” concerto and a faux-flashy cadenza — a new leader is victorious, but in the background, wild, virtuosic tolling bells call to mourn the dead. There is an irony of history: this work’s title had emerged before “variants” came to be synonymous with public health crises; its meaning has only multiplied since.

In contrast to these darker images, Christopher Castro’s Beethausenstro-Castockhoven, a portmanteau of his name with Beethoven and Stockhausen (worth trying to say out loud), assumes a decidedly goofier tack, poking fun at the aggressive showmanship of 25-year-old Beethoven and the absurd galactic proclamations of Stockhausen. Deconstructing the pointed, two-bar introduction that begins MANTRA — what Stockhausen grandiosely described as “the shortest introduction in the history of music” — Castro decides to expand this introduction, allowing it to develop like an infinite crystal structure, gradually bursting at its seams. Both pianists are assigned auxiliary instruments — the same Japanese-style woodblock required for MANTRA, as well as kickdrums and brake drum — lending a kind of “trash heap sinfonietta” character to the whole work.

To conclude this multifarious medley, Laura Cetilia offers us a kind of calming meditation in sense of missing. Yin to our rageful Yang, Cetilia decided to focus on a more positive image, yearning, as co-author to the emotions that lead to anger in the face of loss. Both pianists are asked to weave pennies between the piano strings (pennies that are decidedly not lost) to create complex gong-like tones. The pianists are given a sequence of rhythmic motives from the Beethoven which they repeat at will, freely choosing from provided pitches, creating counterpoint and harmonic collisions out of focused coincidences, “mirroring how two separated people may drift towards, away, alongside each other throughout their lives despite their binding desire to be reunited.”

As a final chapter in this collection of musical sedgeflowers, we end with an introduction, Christopher Stark’s Foreword (2017), the first piece we commissioned as a companion to MANTRA. Chris was, in many ways, an inspiration for this project. As a recent graduate of Cornell University, he taught one of the first classes I took as a new doctoral student, an introduction to electroacoustic techniques that ultimately led me down the path to tackling MANTRA with Andrew. Chris has served as our sound diffusionist for MANTRA on several occasions, and as a student I distinctly remember Chris describing Stockhausen as “one of the friendliest composers from an audience’s perspective,” in the sense that, like a great film director, he always knew when it was time to cut to a new scene. Foreword was composed as a way to prepare the audience for the timescales explored in MANTRA, the static harmonies, the motivic obsessiveness, and the moments of structural dissociation. As an homage to Stockhausen’s interest in the cutting-edge, Chris includes a computer processing element that turns the sound of the two pianos into an infinite hall of mirrors. Cascades of distorted, Dali-esque arpeggios pass between the two instruments, accentuated by the chirping of synthesized tones that endlessly chase the two pianists like a glitchy digital shadow. The work ends with dry, percussive clattering in the upper registers of the pianos (muted by scattershot-filled beanbags) that evokes the iconic woodblock strike at the beginning of MANTRA. As with the Stockhausen, everything is circular: musical structures appear with no clear beginning or end and develop infinitely until the performers “decide” to turn them off. This is not music that “communicates” in a traditionally linguistic sense, but instead behaves like a delicately balanced ecosystem.

Andrew and I hope that you will give yourself the time and space to listen through this album in its entirety, taking in the vast aesthetic chasms in this extraordinary collection of works, and remembering that “the present moment” is only ever a blip on a galactic timeframe. The calm and focus lent by this realization will be necessary for the decades to come, which may make the twentieth century look like little more than a foreword. —November, 2024

The Genesis of MANTRA

by Paul V. Miller

To say it as simply as possible, MANTRA, as it stands, is a miniature of the way a galaxy is composed…I’ve never worked on a piece before in which I was so sure that every note I was putting down was right.

—Karlheinz Stockhausen in conversation with Jonathan Cott (1973)

A monumental work of over 70 minutes, MANTRA both synthesized Stockhausen’s earlier compositional techniques and set the stage for the next 25 years of his creative endeavors. Although it is a rigorously structured piece, MANTRA is not hemmed in by its elaborate plan. Its sound world provides an abundant feast both for those acquainted with Stockhausen’s idiosyncratic approaches, and for casual listeners who simply want to enjoy a “theater piece for two pianos.” But MANTRA’s world of sound glimmers more brilliantly in proportion to the amount one has studied its internal clockwork. Stockhausen understood this, and recorded a comprehensive set of English-language lectures on the work in July 1973 at the Imperial College of London (all of which are currently available on YouTube). Having listened to and studied the piece myself for over 20 years, I was delighted to be asked to offer my own thoughts regarding MANTRA’s genesis, concrete elements, structure and meaning, to accompany this remarkable new recording by virtuoso pianists Ryan McCullough and Andrew Zhou.

MANTRA is basically an extended work for two pianos. In addition to their respective instruments, the keyboardists each perform on their own set of 12 crotales (antique cymbals) and woodblocks (specifically, Japanese woodblocks called mokusho). The pianists also operate a shortwave radio (or a recording of one) and two ring modulators. These last elements are some of the most unusual aspects of MANTRA. Combining acoustic and electronic sounds in a single work was something Stockhausen had ample experience with, going back to KONTAKTE (1958–60). The Dutch pianist Ellen Corver, who recorded all of Stockhausen’s piano pieces under the composer’s direction, wrote that MANTRA’s particular combination of acoustic and electronic instruments achieved “the complete balance of all the different phases within the composing of Stockhausen, the perfect synthesis.” How did Stockhausen get the idea for such a piece?

MANTRA began as a scribble Stockhausen made on the back of an envelope during a car trip through New England in September 1969. Recalling the moment of inspiration, Stockhausen said to Jonathan Cott:

I just let my imagination completely loose…I was humming to myself…I heard this melody—it all came very quickly together. I had the idea of one single musical figure or formula that would be expanded over a very long period of time, and by that I meant fifty or sixty minutes. And these notes were the centers around which I’d continually present the same formula in a smaller form.

Less than a year after this first sketch, the entire score was complete. Longtime Stockhausen collaborators Alfons and Aloys Kontarsky premiered the piece at the Donaueschingen Festival in October 1970 just two months after its completion. The duo recorded the piece the following year, and performances in Shiraz (Iran) and elsewhere soon followed. The music appeared in 1975 in a meticulously neat, handwritten score, as one of the first publications of Stockhausen’s own personal publishing house.

For a decade preceding MANTRA, Stockhausen had progressively stripped away traditional musical notation from his scores. Works such as PLUS-MINUS (1963), SOLO (1965–66), SPIRAL (1968) and KURZWELLEN (1968) employ an idiosyncratic language of graphic symbols such as plus, minus or equal signs that performers interpret. AUS DEN SIEBEN TAGEN (1968) took this tendency to the extreme. The score consists only of fifteen texts or poems. Jerome Kohl argued that these texts contain hidden information regarding types of musical processes that the performers use to improvise “intuitively.” Radically unlike its direct ancestors, MANTRA is an entirely deterministic piece: that is to say, every note is written down in traditional musical notation.

At its simplest, the titular “mantra” is a series of 13 notes consisting of a tone row of 12 distinct pitches, plus the first note repeated at the end. The first event one hears in the piece is the entire mantra compressed into four block chords, followed by a tremolo on A, the mantra’s first note. A full presentation of the mantra follows, but, as is typical for Stockhausen, it is not a simple didactic recitation. Rather, each note is associated with a particular kind of articulation or ornament. The characteristics are as follows (compare with opposite page):

Note Pitch Characteristic

1 A Regular repetition

2 B Accent (at the end)

3 G-sharp Normal

4 E Grace-note group around the central note

5 F Tremolo

6 D Chord (accented)

7 G Accent (at the beginning)

8 E-flat “Chromatic” connection (grace notes)

9 D-flat Staccato

10 C Kernel for irregular repetition (“morse code”)

11 B-flat Kernel for trills

12 G-flat sfz (fp) attack

13 A Arpeggio connection

While the first pianist’s right hand plays the mantra — with each note expressing its corresponding character — the left hand plays an inverted version displaced by one phrase: for example, ascending contours in the first bar of the right hand become descending ones in the third bar of the left hand, and vice-versa. This resembles the invertible counterpoint of a traditional two-part counterpoint exercise, lending this opening a decidedly “antique” mood. This music is divided into four segments, each separated by a rest of varying durations. With each pitch in the right hand expressing a distinct character, and the mantra in counterpoint with itself, this whole complex becomes the work’s “formula.”

MANTRA is essentially an enormous expansion of this formula over a timespan of more than 70 minutes, pursued systematically over the course of 13 sections, one for each note of the mantra. The antique cymbals announce the beginning of each new section. Within each section, Stockhausen takes the formula and presents it twelve times. But whenever we hear the formula, it is at one of twelve different speeds. Its tonal structure is also usually altered, sometimes radically so. Stockhausen devised twelve different musical scales or “expansions” [Spreizungen]. These range from the most compressed and conventional (a chromatic scale) — as heard in the introduction — to the most spread-out form that can fit on to the piano keyboard (three octaves plus a minor sixth) accounting for the various transpositions. By mapping the mantra pitches onto the notes of these variously spread-out scales, Stockhausen devised twelve distinct tonal realizations of the formula. The permutations of the temporal and pitch expansion are determined according to a serial process: essentially, the relentless rearrangement of a simple number series.

In each section, the tonal expansions in piano 1 begin on a successive note of the mantra. Consequently, in section 1 each mantra presentation starts on A; in section 2 each presentation starts on B, etc. The second piano follows the same principle, but begins its permutations on the inverted notes of the mantra. As if this were not enough, additional complexity arises as Stockhausen permutes the articulation characters enumerated above, “intermodulating” each temporally and tonally altered statement of the mantra accordingly. These novel features present Stockhausen with innumerable opportunities for finding innovative ways to realize the mantra, both on a local and global level.

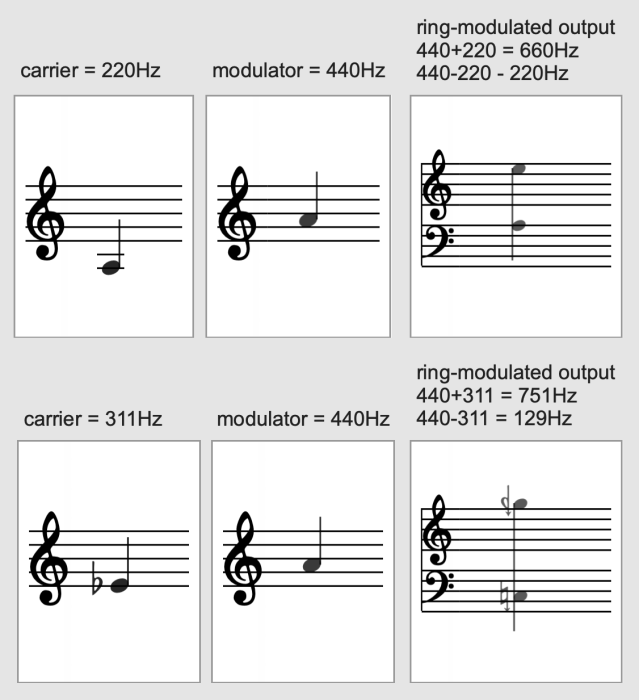

Stockhausen used a different, more sensual method to organize the large-scale sequence of sections in MANTRA, now through electronic means: namely, ring modulation. This signal processing technique was invented in the 1930s and takes its name from the circular arrangement of four diodes that lies at the center of its electronic circuit. In MANTRA, the carrier signal is always a sine wave, and the modulator signal is the sound of the pianos themselves, picked up by microphones placed in the instruments. While it is possible to produce ring modulation using analog circuits, these can be temperamental and prone to failure. In this recording, Mr. McCullough wrote a patch in the software environment Max/MSP to produce the effect digitally. The effect of ring modulation ranges from quite subtle to dramatic. A ring modulator essentially produces an output signal consisting of a pair of sideband frequencies: the first is the sum of carrier and modulator, while the other is the difference. For example, if the sine wave input is an A at 220 Hz and the piano frequency is an A one octave higher at 440 Hz, the ring modulator produces one tone in unison with the original A (440 – 220 = 220 Hz) and another an E above (440 + 220 = 660Hz). This is a relatively “harmonic” sound, because E lies a perfect fifth above the original A. On the other hand, if the sine wave input is E-flat (311 Hz) and the piano plays A (440Hz), the outputs are a C slightly lower than the equal-tempered C on the piano (129Hz,) and a microtonal note somewhere between F# and G (751Hz). This results in a much more dissonant, bell-like sound than the first example, since ring modulators will often produce more complex sidebands as the carrier and modulator signals themselves become more dissonant in relation to one another.

Over the course of MANTRA, the pianists adjust the frequencies of their sine wave generators at the beginning (or near the beginning) of each section, corresponding to each successive note of their mantra form: either right-side up, or—in the case of the second pianist—inverted. Consequently, the first and last notes of piano 1’s mantras always correspond to the sine wave input in each section. However, the second pianist sets the sine-wave input frequency to the inverted notes of the mantra, so piano 2’s output signal is often more dissonant. The resulting effect is that each of the 13 large sections in MANTRA has its own particular timbre, caused by the ring modulator effect.

In several sections, the pianists change the frequencies of their sine waves continuously, as a glissando. This creates an astonishing timbral effect unlike anything the pianos can do on their own. One excellent example of this occurs in the fourth section (bar 109, 1:32 in track 4), where the pianists continuously vary the frequency of the sine wave inputs to the ring modulators while playing slow chords, maximizing the otherworldly, shimmering effect. This happens elsewhere in the score, often in moments where Stockhausen desires an especially sublime musical texture that transcends the fixed, equal-tempered piano tuning.

Amusing theatrical aspects abound in the score of MANTRA. Many of these occur during so-called “inserts” [Einschüben]. In such sections, Stockhausen suspends rigorous structural processes, instead writing music that seemed right to him in the moment. The Stockhausen scholar Richard Toop was fond of calling inserts “serially unauthorized” moments. Before MANTRA, Stockhausen frequently used this technique to counterbalance the strict serial structures he set up. Sometimes insertions also carried personal significance for him. While composing the electronic composition STUDIE I in 1953, Stockhausen received a phone call from the hospital that his first daughter Suja was born. At that exact moment, Stockhausen took a random strip of magnetic tape from the studio floor that had some noise on it and spliced it into the composition. Insertions continued to play important roles in many compositions after MANTRA, such as when the janitor interrupts the ending of WELT-PARLIAMENT — the first part of Stockhausen’s opera MITTWOCH AUS LICHT [“Wednesday from Light”] — to announce that an illegally parked car is about to be towed away.

Because there are four rests in the formula separating “limbs” of the mantra, there are also four inserts in the larger work. The first occurs in the fifth section (bar 212, 0:32 in track 6) and involves the repetition of just a few notes. It is as if the composition has become “stuck” somehow at this moment. At a certain point, the first pianist mischievously plays a “wrong note.” The other pianist “laughs” and corrects the obvious mistake. An amusing disagreement occurs over what the correct high note should be; the second pianist becomes extremely irritated and repeats the correct note over and over again as a tremolo. After finally resolving their disagreement amicably, the pianists continue along as before.

The fourth and final insert is perhaps one of the most astonishing pieces of musical invention of the twentieth century. In the thirteenth and final section, (bar 692, 2:40 in track 14) the pianists suddenly launch into a section marked “sehr schnell” (very fast) in which every note of the composition is repeated, as sixteenth notes, in a kind of “toccata meccanica” style. Both “mechanical” and “manic,” crashing block chords increasingly dominate the texture, until the insert dramatically ends some 150 bars later. Hermann Conen calls this insert a “coda” while Toop characterizes it as a “cadenza.” Both terms are valid; the ultimate effect is probably intended to make the final return at the very end of the piece more satisfying.

For the listener acquainted with MANTRA’s basic plan, the inserts are relatively easy to pick out. But Stockhausen found ways to insert private humor as well into MANTRA. As mentioned above, the note A (440Hz) is both the first and last note of the mantra; it is also the last note of the whole piece. At bar 440 in the score (10:59 in track 7), Stockhausen wrote the words “‘s ist alles nicht so tragisch” (“It’s not all that tragic”). Because this scribble in the score is impossible for the audience to know about, it becomes a kind of “inside joke” for the performers themselves.

In addition to the ring modulators, Stockhausen features another unusual electronic element: shortwave radio. This makes its grand entrance in track 10 around the 3:10, where the dominant character is “irregular repetition (Morse code).” The sound of radio broadcasts, which were so ubiquitous at the time of MANTRA’s composition, play a central role in several of Stockhausen’s earlier compositions. The shortwave radio brings unpredictable, sometimes humorous and occasionally mysterious sounds into the concert space. The performance is opened to unforeseeable effects from foreign cultures, musics, and even possibly phenomena that originate from within other planets, stars or galaxies. Nowadays, the shortwave radio spectrum is more silent than it was fifty years ago, so this recording uses a tape that Stockhausen himself produced, kindly provided to the pianists by Kathinka Pasveer of the Stockhausen-Verlag.

An almost deafening tremolo of antique cymbals announces the mantra’s final statement. This points to the dual role these metallic instruments play in MANTRA. On the one hand, they clarify the form by signaling the beginning of each section. On the other, they remind us of religious ritual; many faiths across the world incorporate these small cymbals into their ritual practice.

The final presentation of the counterpointed formula is conspicuously laid bare, intoned without any of its embellishing characters, stripped down to its essential simplicity. For all its technical and theatrical bravura, Stockhausen would surely agree that MANTRA is ultimately a spiritual work. As Gavin Flood writes, mantras are “central to the ritual traditions of Hinduism.” They are given orally to students by their teachers or gurus, and recited to produce mysterious energies or forces. Through its “systematic pursuit of variety” (Toop), MANTRA strives to produce a similar, powerful effect within its listeners: to bring into being a positive energy, to transform the spirit to a higher level, and to hasten a galactic consciousness that surpasses material existence. — August, 2024

Paul Miller is professor of music at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, PA, where he teaches music theory and specializes in historical performance and electroacoustic music.